The View From the Road (2015 – ongoing)

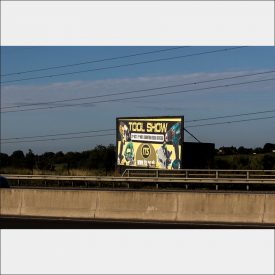

During a House of Lords discussion in December 2004, the Labour peer Lord Sheldon noted that trailers parked in agricultural land were “pretending to be on their way to somewhere and holding advertisements”. On both sides of the House, there was concern that the trailers flout planning regulations, whereby they circumvent laws prohibiting fixed advertising boards by the side of motorways (UK Gov, 2004). The View from the Road is a visual arts project that explores these billboards and the mutations by which they continue to thrive. Through case studies from South East England, it seeks to position the billboards in relation to ecology, sociologies of mobility, aesthetic politics, and political histories of land use.

The project takes the form of walking workshops, speculative architectural modelling, drawing, investigative journalism, photography, talks and presentations. Interpretive and theoretical frameworks include: art history, the sociology of mobility, non representational theory, political geography, and spatial theories that inform art, architecture and urban studies. To an art historical cannon dominated by representations of static billboards in the US context, it brings a new billboard typology and a new geographical context. It asks: How might aesthetic enquiry into the billboards contribute to their critical appraisal? These investigations reveal how the billboards constitute a new and specific configuration of land, landscape, landownership and vision under the conditions of neoliberal democracy in the UK. In this respect, they help write the complex social and political histories of England’s countryside, and have cultural heritage value. Additionally, they (the investigations) contribute to discourses of vision, the subversion of clear vision, and re-visioning the relationship between the highway and the places through which it passes. They bring the project into proximity with the sociology of mobility which, since the first decade of the twentieth century, has sought to articulate a research paradigm able to capture concepts such as networks, passage and flow.

Outputs have taken the form of online artworks hosted by Future Architecture Platform and the Stanley Picker Gallery, a book chapter, and a visual arts exhibition at Goldsmiths, University of London. The project will interest students, scholars and wider audiences of visual cultures, mobility studies, and the politics of landscape.

Research Context

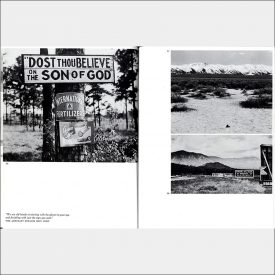

Since at least 2004, Government, businesses, and non-profit organisations such as the Countryside Alliance have discussed the rise in roadside advertising that exploits a loophole in UK law. Within the visual arts, critical approaches to billboard landscapes is indebted to the pioneering work of pop and post pop artists such as Peter Blake and Ed Ruscha in the 1960s and 70s. In his provocatively titled book God’s Own Junkyard, Blake presents the US as an Eden transformed under unchecked capitalism, condemning the billboards as ‘scars’ and ‘pestering sores’ that blight the landscape (Blake, 1964: 125). Blake’s writing has assumed a concept of landscape in its art historical, Romantic sense: the pictorial. However, his prose is offset by rich illustrations that signal a more ambivalent relationship to the places he has visited. In this alternative presentation, landscape is taken to be a territory subjected to a mapping impulse of detailed, disinterested observation. Thus, Blake’s project drew attention to the presence of two rival concepts of landscape. It also positioned artistic enquiry into billboard landscapes as an instrument with which to investigate these concepts. It did not, however, significantly advance understanding of the relationship between these concepts or of how they relate to wider theories about the pictorial, observation and the politics of land.

Ruscha takes the billboards that punctuate the rural and urban landscapes of southern California as material for his art. His treatment, one of cool reserve and devoid of judgement, is decisively indebted to the mapping impulse. It is also a way of playing out an artist’s persona that was gaining traction by the 1960s, as theorised by historian Moira Roth in her essay The Aesthetics of Indifference (1998.) Roth understood this persona as delivering a critique of the oppressive political regimes of the time and argued that it was played out in pop’s indifference to the subjects it investigated. Although not discussed by Roth, Ruscha’s billboards also exemplify the critique she identifies, signalling that this body of work belongs at the forefront of critical enquiry into the relationship between artistic vision, territory and liberal political thought.

In his PhD thesis Ferguson explored the relationship between vision and power. He argued that vision is inherently interested and proprietary, and that clear vision is foundational to extraction economies and its attendant political and social oppression. If these colonial patterns of thought are to be broken, then the interruption of clear vision, actual or symbolic, might play a part in the process. This project takes up the problem through an investigation of landscape. It is in part an attempt to see whether an landscape can make a claim upon the imagination independently of desire. To see whether it can escape the gaze and become a thing that acts independently upon the subject.

The relationship between the road and the places through which it passes has engaged commentators across the arts and social sciences, particularly within the disciplines of architecture and film studies. In film, for instance, the car windscreen has been imagined as a cinematic screen on which an ever-changing view is projected. Paul Virilio’s essay on apprehending speed, Dromoscopy (1978), is both pioneering and exemplary in this line of thought and Iain Borden’s 2013 book Drive has provided a valuable survey of how the experience of seeing from the car has been represented within the medium.

The process of dromoscopy is taken up in the visual arts by artists Robert Smithson in Incidents of Mirror Travel in Yukatan (1971) and Rachel Lowe in Letter to an Unknown Person (1996). For both, the car window provides a a framing device that, when moving at speed affords a method of viewing landscape which subvert’s landscape painter’s slow, privileged attention in which the land is orientated towards the subject’s acquisitive mind. In this way the fleeting landscape conditions a shallow, almost indifferent gaze. The reappraisal of the driver’s gaze finds further treatment in Michael Schwarzers Zoomscape where the author notes: ‘Driving encourages a nonchalant way of looking.’ (2004: 72). If, as I have argued in my doctoral research, artistic attention has its origins in the aristocratic affectation nonchalance, then the billboards that line the highway in South East England suggest themselves as an opportunity to test the possibilities of dromoscopy as a mode of attention, or method adopted by the art researcher.

Dromoscopy is also implicit in the spectatorship of Anthony Gormley’s Angel of the North, a colossal steel sculpture commissioned by Artangel and completed in 1998. Gormley’s work stands 20m tall and 54m wide on a hill next to the A1 Motorway just south of Gateshead, UK, and can be viewed from a distance of several kilometers by motorists passing from either direction. The departure that Gormley makes from the previous examples in the visual arts is first, that it is a type of viewing practice adopted by the art goer rather than the artist, and second, dromoscopy is an absolute condition of tourism, whereby its practice is a function of the fact that it is simply impossible to stop.

The arrival of billboards in the UK countryside offers a fresh opportunity to explore these ideas further. Of particular interest is their mobility and their use of agricultural land as this is seemingly a new phenomenon that promises to shed light on changes in land use and interpretation under free market capitalism. Their relationship to the road opens new possibilities in philosophies of vision. In the context of the discipline of art practice, the billboards also suggests new avenues for the exploration of the aesthetics of indifference

Methods and Processes

1. Development of a proposal to use a billboard for a public artwork.

- Thinking: speculating/imagining

In order to make space in which to think about what kind of knowledge the project would try to produce – to arrive at questions -, a pretext was invented for investigating the billboards. This took the form of a proposal to use a roadside billboards as a site for a public artwork. As an established art form in itself, the proposal medium would open up insights to be gleaned from the various processes required for its development – forays into the countryside to visit billboard sites, hiring one, designing an artwork – without necessitating its realization. In this way it would facilitate the production of knowledge non-representationally (i.e. through embodied experience), and without having to negotiate the political reality of installing a work adjacent to the highway. It was clear from the outset that, on account of the illegality of the billboards under scrutiny, and the distraction to drivers that would be posed by an artwork that made use of one, a publicly funded commission was unlikely to be realised.

- Sensing: Dérive

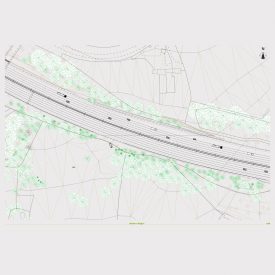

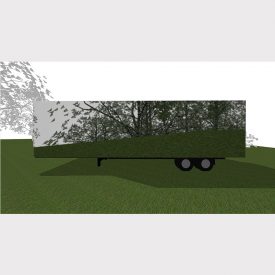

In search of a site for the proposal, between 2012 and 2015 Ferguson and collaborator Richard Beard visited and photographed mobile billboards parked on agricultural land adjacent to the M25, the M40 and A12.

The hope was for a revelatory event in the early stages of the proposal development that would form a beginning of the artwork’s concept.

- Sensing: Driving at speed

Driving at speed past the billboards was instrumental in the development of a concept. The difficulty posed by photographing the billboards at speed was at odds with the mastery of landscape familiar in both art and visual culture more widely. This observation provoked questions altogether more specific than those that had occasioned the forays in the first place: For instance: How is the category place affected by the inattention that characterises the drive-by gaze? That is to ask: how is it affected by the curtailment of phenomenological knowledge, so that discrete objects – buildings, trees and even people – are potentially reduced to imagistic fragment? Might the experience of seeing at speed provide a critical apparatus through which to disrupt economies of clear vision, value extraction, and oppression?

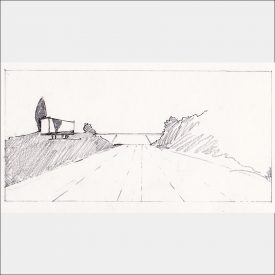

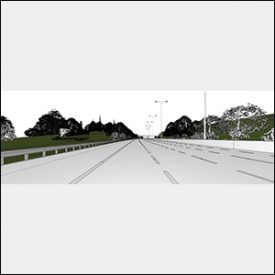

The core concept emerged from these beginnings. The proposal would be to depict on the billboard a landscape that promised to be pleasurable to view, but to present it in such a way that this pleasure was repeatedly frustrated.

- Presenting

Emerging ideas were presented informally in a range of forums – the pub, dinners and on one occasion a living room in Wells Street, Hackney, where a curator friend invited other artists and curators to see the project in progress.

- Modelling

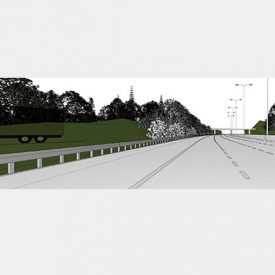

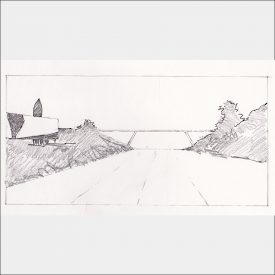

Using 2 and 3D modelling techniques, experiments were made with frustrating the view.

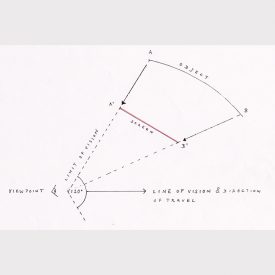

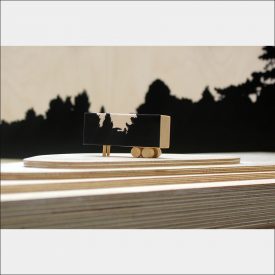

The leading idea was realized digitally in collaboration with architect Joseph Lythe. The billboard would be printed up with a view of the landscape in which it was positioned. As the motorist past the billboard, the image on its surface would line up with the background. However, this would take place only as the billboard passed from view.

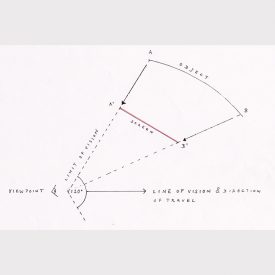

Experiments with print media for production of the artwork that would be affixed to the trailer. These involved the use of anamorphic projection diagrams to calculate the required correction to the image so that it coincides with the background landscape when viewed from the road. Three full scale fragments of the billboard were printed onto blue backed billboard paper each measuring 1m x 1.8m.

3D diorama modelling to convey the proposal in physical space. Location. Fulmer House Farm. M40 westbound.

6. Archaeology

- Removal of the surface paint concealing a logo on a trailer to identify its provenance.

- Photographing the trace of the logo and reproducing its design using Adobe Illustrator.

- Attempting to match the uncovered logo with those of haulage companies past and present.

- Land search to establish the ownership of a field where one of the billboard trailers was parked.

- Historical and economic research into highway landscaping, roadside ecology, and economic values of land adjacent to the highway.

Outputs

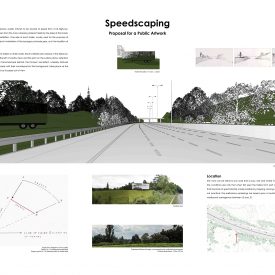

- Speedscaping: Proposal for a Public Artwork (2015) Exhibited Goldsmiths Art Research Space. Feb 23 – Mar 5, 2015

The proposal comprises four exhibits. (i.). Poster. (ii.) 3D diorama model. (iii.) Billboard fragment. (iv). Digital drive past

Speedscaping: Proposal for a Public Artwork was exhibited in the Goldsmiths Art Research space in 2015 and the poster exhibit is hosted online with Future Architecture Platform at this address.

- The Mobile Landscape (2015)

The Mobile Landscape is an online artwork hosted by The Stanley Picker Gallery, Kingston Upon Thames. Link to online artwork

- ‘Speedscaping’. In: Mackay. R. 2015. Urbanomic.

Speedscaping is a book chapter comprising images and a text that discusses the project. It was commissioned by Robin Mackay and funded through Goldsmiths.

Link to: When Site Lost the Plot.

Link to Kingston University repository for book chapter details: https://eprints.kingston.ac.uk/33801/

Observations

Through exposure to the billboard sites and various acts of making that include speculative modelling, photography and curatorial practices, it was possible to stage a reappraisal of the value of roadside advertising hoardings in South East England. The project signalled their cultural heritage value and a role in understanding the complex social and political histories of the countryside. It also contributes to critiques of economies of clear vision and experiments with its subversion.

Through the mediums of performance lecture and online artwork, the project questions dominant discourses of the highway as a ‘non-place’ and the Highways Agency’s positioning of the countryside as space to be traversed. It shows instead that a highway is richly connected and interdependent with the territory through which it passes and that communities near or adjacent to the highway have adapted to being viewed at speed. These changes belong within a longer history of England’s changing land use. The billboards contribute to what urban theorist Neil Brenner has called an operational landscape – a capitalist form of urbanisation that “transforms non-city spaces into zones of high-intensity, large-scale industrial infrastructure”(2016:125) As such they are an aesthetic manifestation of neoliberal democracy bearing material witness to the aesthetic indifference of free market capitalism.

Through the medium of the proposal, the project prompts reflection on the visual and conceptual separation between the road and its context. Though the same medium, it brings the concept of dromoscopy – seeing at speed – in contact with artistic strategies of disruption. The motorist/viewer is denied the pleasure of a harmonious, integral landscape orientated to his or her gaze. If the billboard is a category of architecture, then architecture is assigned a future role as playful commentator on the impossibility of a satisfactory view of place when seen at speed.

There are inescapable structural parallels between art practice’s critical methods of aesthetic indifference, and the liberal logics of free market economics that have produced the billboard landscapes in the UK. During debates in the House of Lords, while the issue of safety is raised in the discussion, the complaint against them on both sides of the house that they and spoil the scenery (UK Parliament, 2004; 2010). The fundamental problem, is not one of safety, but aesthetics – an ideological rather than practical problem – raising political questions about what the countryside is for and who its primary beneficiaries should be. As if by way of signpost through this contested terrain, at a further discussion of the topic in 2010, the Conservative peer Lord Forsyth contended that there is nothing wrong with a bit of free enterprise on the part of landowners and advocates that the government steps back from interfering (2010). Aesthetic indifference, in the form of market logic, would be the basis on which judgement was to be passed. Not least, they both turn on a notion of indifference – liberalism via the principle of laissez-faire, art via the concept of aesthetic attention – whereby various forms of interestedness are suspended.

References and Bibliography

Alpes, S. 2005. The Vexations of Art. Velazquez and Others. Newhaven and London, Yale University Press.

Appleyard, D. Lynch. K and Myer J. 1964. The View From the Road. Cambridge Mass.

Ballard, J. 2014. Concrete Island. Fourth Estate.

Blake. P. 1964. God’s Own Junkyard. Henry Holt & Co.

Borden, I. 2013. Drive. Journeys Through Film, Cities and Landscapes. Reaktion Books.

Brenner, N. 2016.The Hinterland Urbanised. AD / Architectural Design, July/August, 2016, 118-127. Available at: http://www.urbantheorylab.net/publications/the-hinterland-urbanized/

Copely. S. 2010. The Politics of the Picturesque: Literature, Landscape, and Aesthetics Since 1770. Cambridge University Press

Cosgrove. D. 2012. Geography and Vision. I B Tauris

Grabner, M and Killam B. (n.d) The Poor Farm. Available at: http://poorfarmexperiment.org/about/

Gray, E. 2005. Don Juan and the Poetics of Tourism. In: Poetry and Indifference. From the Romantics to the Rubáiyát. Amhurst and Boston: University of Massacusetts Press

Jacobsen. K, Leming. W. 2013. American Road. [DVD] Cold Chicago Productions.

Lowe, R. 1996. Letter to an Unknown Person. Available at: http://visualarts.britishcouncil.org/exhibitions/exhibition/landscape-2000/object/a-letter-to-an-unknown-person-no-5-lowe-1996-p7171

Merriman, P. 2007. Driving Spaces. A Cultural-historical Geography of England’s M1 Motorway. Wiley-Blackwell.

Mitchell. W. 2002. Landscape and Power. University of Chicago Press.

Petit, C and Sinclair, I. 2002. London Orbital. DVD.

Roth. M. The Aesthetics of Indifference. In: Roth. M. 1998 Difference/Indifference. Musings on Postmodernism, Marcel Duchamp and John Cage, Critical Voices in Art, Theory and Culture. Routledge

Ruscha. E. 1966. Every Building on the Sunset Strip. Los Angeles. Self Published.

Schwarzer. M. 2004. Zoomscape. Architecture in Motion and Media. Princetown Architectural Press

UK Gov. 2004. Parliamentary Business Publications and Records. Available at https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld200405/ldhansrd/vo041215/text/41215-03.htm

UK Gov. 2010. Roads: Illegal Motorway Advertising. Available at: https://www.theyworkforyou.com/lords/?id=2010-07-21a.967.5

Vertov. D. 1929. Man With a Movie Camera. DVD

Virilio, P. 1998. ‘Dromoscopy, or the Ecstasy of Enormity’. Trans. Edward O’Neill. Wide Angle 20.3 (1998) 11-22