Pandemic Landscapes. Observations from London Heathrow

A much revised version of this work is now available in the journal Futures. For the interdisciplinary study of futures, anticipation and foresight. To download a PDF, click here

Abstract

In this photo essay I present on the experience of Heathrow Airport under the conditions of the first national lockdown in England, March – June 2020. I bring together images of Heathrow, planetary social thought, and aesthetic reflections on the modern ruin. The essay relays how the airport, ordinarily a space of weakened phenomenological experience of the past, reverted during the pandemic to one in which history was acutely felt. For as the excesses of the present moment receded, so did their capacity to distract. Into view came an urban fabric tailored to needs that were no longer. But as well as a vanishing past, the scene was unavoidably also a catastrophic future. For in the context of growing awareness of climate change and the pervasive anxiety that characterises our time, the landscape was also allegorical, offering pause for thought on the dystopia of the present and the need to act. To this extent, even if the airport’s services were to recover, the cultural reception of its promise may be irredeemably altered.

Keywords: art and mobilities; Covid-19 pandemic; environmental futures; Heathrow airport; modern ruins

“I thought the Museum of Civilization was a rumour,” August said.

“What is it?” Kirsten had never heard of it.

“I heard it was a museum someone set up in an airport.”

Emily St. John Mandel. Station Eleven. Picador, 2015. p124.

I.

London, May 2020, six weeks into the first COVID-19 lockdown. About halfway along the northern edge of the Perimeter Fence of Heathrow Airport, there is a lone Ford Mustang in Business Parking (Fig1). To see it, I have left home legitimately for exercise, but more truthfully to witness first-hand the remarkable pause that the pandemic has forced on the global aviation system.

The Mustang has been here for several weeks. It is likely to belong to a male (I’ve checked the demographic), a businessman who travelled abroad as the pandemic struck and is now unable to retrieve it. Perhaps he is Pierre Dupont, the protagonist in Marc Augé’s seminal anthropological text non-Places (1995). Dupont is a French businessman, though he could be from anywhere in Europe, whose very average journey to work takes him through places devoid of identity, history or social relations. Augé tells us he travelled to the airport along the autoroute, paid my means of a machine, parked in Row J and, aboard the plane, immersed himself in the inflight magazine. So all pervasive, so utterly absorbing is the present for Dupont, that there is no sense of what has gone before or of what is to follow. An ever expanding and endless stream of technology, entertainment, advertisements, all of which necessitate choices, decisions, and arbitrations on the now – displaces all other temporal experience. Dupont’s lifestyle is one of total presentness and the epitome of supermodernity. The international airport is his native environment.

Augé puts no date on Dupont’s experience of presentness, but details of the spaces and technology leave no doubt it is the early 1990s. If Auge’s book may be taken as a pioneering attempt to articulate a new and universal kind of experience, then the abandoned car would seem to suggest the need for an update to this narrative. We could think of the car as a figure for Auge’s world view on pause. Like a ruin, it gives pause for thought on what it was about and what will replace it. What follows is in part a response to this figure.

I say in part” because, at the same time, the scene is also suggestive of a catastrophic future. This equally allegorical interpretation plays on the potential of a deserted place now to suggest another to come. The idea was theorised by Walter Benjamin when he wrote: “Just as there are plants that are said to confer the power to see in the future, so there are places that possess such virtue. For the most part they are deserted places [in which] it seems as if all that lies in store for us has become the past” (2006: 79). Benjamin went on to articulate the political potential of the ruin’s providential capability, arguing that it breeds in the spectator a kind of eschatological consciousness in which catastrophe is a pre-requisite for organising something different (2009). Today the threat of climate change, ecocide and human extinction add a specificity to Benjamin’s theorisation quite different to any that he is likely to have imagined. Moreover, they require that we link the pandemic landscape with that of human disappearance resulting from climate change. This is second thing my paper will respond to.

My interest in the ruins of presentness is pursued within the disciplinary field of artistic research. Art is taken as both methodology and object of study. At the centre of art led methodologies is a geographically situated body that, as Henk Slager has argued, releases first-hand experience of the world into a loose web of interpretive possibilities.[i] At the same time the field of art practice has staked its reputation on the ability to make perceptible by honing visualisation techniques that as Jonathan Crary has argued, permit novel ways of seeing. My engagement with the medium draws especially on a tradition of documentary photography and art writing that experiments with the consubstantiality of practice and theory, criticism and experimental processes.

It is my explorations of this field in the Heathrow context that has attuned me to the presence of artworks at Heathrow. In the present context, I am interested in how these works, all commissioned by the airport or the airline British Airways have fared in lockdown and how, in turn, the pandemic has necessitated their revaluation. In this connection, I shall suggest that the pause has laid bare previously less visible aspects of art at Heathrow and raised ethical questions about airport patronage of the arts more widely.

The timing of this enquiry is admittedly insensitive. Key workers in hospitals, shops and schools are putting themselves at risk in their everyday work. Others are fighting for their jobs and livelihoods. The dead are mounting in mortuaries, in some cases former airports (Parveen and Walker 2020). It is hardly the moment to be thinking about lessons. At the same time, the timing could not be better. Lockdown has brought many of us a break from commitments, granting time for reflection. This may soon be taken away. What is more, as witnessed with the abandoned car, the view of the airport in lockdown contains truths not ordinarily present. If these are to be apprehended before lockdown is lifted, there is no time to lose.

II.

A huge amount has happened since the Mustang was left in row J. Human populations have shut themselves away. In fear of their lives, or unable to stay put, many have organised themselves into their respective nationalities and returned home. Factories have halted production, leisure centres and museums shut their doors. The nation state feels more important, the environment more dangerous, international borders less permeable.

Airlines and airports are fighting for survival. The International Airline Group (IAG) who owns the UK national carrier British Airways has lost 75% of its value in just 5 months (International Airlines Group). The workforce is furloughed and there is news of restructuring and mass redundancies. By the summer of 2021 the media will report that air traffic is down 90%. John Holland Kaye, CEO of the Heathrow airport authority, will announce that the pandemic could create ghost towns in the surrounding neighbourhoods. The authority will have shelved its airport expansion plans.

It is not yet clear how Dupont is faring. Augé told us that “[f]or a few hours (the time it would take to fly over the Mediterranean, the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal), Dupont would be alone at last.” It is as if flight cocooned him from the crowdedness of his existence. If he is today confined to an overseas hotel room, he may have found more respite than Augé could ever have dreamed of.[i] But equally, he may have had quite the opposite experience, one in which the pandemic has amplified the struggles and strains of his labour as he clamours to move online. Worse, bearing in mind that he was recently on an aircraft, and that aircraft cabins tend to harbour biological agents, he may have contracted the virus.[ii] Who knows? Today Dupont may be in a hospital bed, a ventilator strapped to his face. Around his car meanwhile the painted rows that once served to communicate the apportionment of concrete are no longer quite legible in those terms. At the edge groundsel has forced its way between the kerb stones reminding us just how quickly nature can take over. In plain in view of the CCTV I have on occasion lingered to take in the view, but nobody has come to find out what I are doing. There is nobody to come.

That an airport might be caught in the past is a remarkable thought. In the cultural imaginary, airports were once places of things to come, ‘thresholds of modernity’ (Pascoe 2001). The French filmmaker and essayist Chris Marker captures this sentiment in the science fiction film La Jettee (1962). Caught in the midst of World War III, a man unwittingly witnesses his own death while standing on the observation deck at Paris Orly. He has been shot on behalf of captors who have facilitated his time travel so that the past and future can be summoned “to the rescue of the present”. Marker’s choice of mise-en-scene registers how spatial exceptionalism in the form of leading technology (rendered through the iconography of jet aircraft, high modern architecture, the public address system) becomes temporal exceptionalism wherein relations of past, present and future are altered. There is at the airport already less of the past and more of what is to come. For a generation of Futurists in early decades of the 20th century and for others who would follow, there had been a social and political optimism about this imaginary. It was as if sites of advanced technology were seedbeds of revolutionary thought, what Raymond Williams would later call emergent culture.[iii] In the case of airports, it is difficult not to assume that this imaginary had to do with the experience of enhanced connectivity, of the wider and more outward looking social relations forged through travel. It will also have had to do with the experience of speed, of things quite literally arriving sooner. Writing in France against the backdrop of the Cold War, Paul Virilio makes the point eloquently, even if he disposes of earlier optimism, in his critique of the increasingly dominant politics of time. He writes:

“The flight deck of warplanes offers a political image of the future, the control panel exposes those who wish to see it the foreseeable evolution of power, veritable crystal balls, the screens and dials make clear the otherwise hazy course of politics to come” (2005: 112).

This sense of advancement finds an equal and opposite approach in the economic sphere. Like the 16th century maritime city of Venice, the 18th century pirate enclaves of the Caribbean, today’s freeports of Switzerland, and deregulated cities (for instance, Hong Kong, Singapore, Abu Dhabi, Monaco, Las Vegas), the airport is ahead because it openly enjoys economic advantage. The epithet ‘duty free’ caries its intention. In urban policy terms, it is an example of a zone variant – an incentivised urban form (Easterling 2016) where there are different laws relating to taxation, labour conditions, jurisdiction, and scale. In a world where economic growth is equated with a state of advancement, as in the phrase ‘advanced economies’, the airport’s exceptionalism positions it, as they say, ahead of the curve.

III.

From the footbridge at Hatton Cross interchange there opens to the north a view of parked up planes (Fig). These and other aircraft visible from other vantage points constitute a large part of the British Airways fleet that has been brought here for storage. In the brave new world of Zoom and Microsoft Teams, they look distinctly analogue. Some form a line about a kilometre in length and which cuts between a row of maintenance hangars and the airport perimeter fence. But so tight is the parking regime that it could be broken up only by removing each plane in the reverse order to that in which it was inserted. Buried about halfway along is a Boeing 747 that announces its sponsorship of British athletes bound for the Olympic Games, Tokyo 2020. Nearby another boasts One World. As well as limitations on space, the stowage arrangements reveal insufficient reserves of equipment. To prevent birds nesting in the engines, the cowlings have been wrapped at either end with polythene sheeting. The famous Rolls Royce badges jostle semiotically with strips of gaffer tape holding everything together.

The logistical headache the pandemic has presented the airline tells us just how finely tuned the whole system is. But it also gives a novel indication of scale. Ordinarily distributed through airspace and airports around the globe, most of the fleet is permanently out of sight. There have been a few times when aircraft fleets have been grounded on mass, but none have been global: the events of 9/11, 2001, closed North American airspace for 2 days with a long-term knock-on effect on passenger demand; the Eyjafjallajökull eruption in 2014 closed European airspace grounding 100,000 flights. The pandemic is the first occasion in the history of aviation when entire fleets from all corners of the globe have been grounded. Accordingly, it has also occasioned for the first time the opportunity to see just how big the fleet is. This revelation is not without paradox: the imperatives of lockdown ensure that only exercising residents and maintenance staff can see them. Nevertheless, even if for only a few, knowledge that normally takes the form of numbers – fleet numbers, journey numbers, passenger numbers, carbon emission numbers – translate into something more graspable and thereby more public, namely the physical experience of a fleet’s volume scaled in relation to a human looking on.

The ability to keep an operation perpetually out of view is highly advantageous when the scale of that operation, were it known, might be cause for concern. It enables it to exist and even expand without raising eyebrows and prompting awkward questions. It helps guarantee the status quo, threatening to stifle both analytical thought (what will be) and normative thought (what should be). However, if the operation comes into view, this advantage is taken away. To this extent the grounding of planes has political promise. By making the sheer number of planes visible, it redistributes power away from the airlines and to those who wish to witness the prospect. In my case, I am given a feel for how many people will normally be flying at any one time. This bigger picture feeds speculation on how my way of life might be impacting on the environment. It thus positions me to make more informed judgements on whether, how often, or how far to fly. For rival transport operators, it will no doubt underscore how the airline benefits from space not available to themselves, the sky, and for the use of which it does not need to pay. For all of us, it gives a sense of how the industry has crept up on us. The grounding of planes brings more than aircraft down to earth.

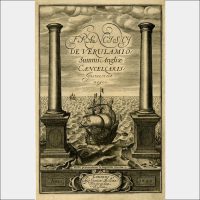

If the abandoned Mustang is a figure for the closure of presentness, then the grounded planes suggest the close of a significantly longer era. It’s beginning finds visual representation in Simon Van de Passe’s famous frontispiece to Francis Bacon’s Instauratio Magna (The Great Restoration) (1620) (Fig). Van de Pass depicts a ship leaving port along with a Latin inscription that says: “Many will travel and knowledge will be increased”. The ship is that of the scientifically minded European heading off round the world discovering, extracting, and collecting. For Bacon this process was, as the title of his book indicates, one of returning the world’s knowledge to a former state of unification, and whose loss is represented in the allegory of Babel. Though the stages by which Bacon’s thought has developed in the intervening centuries are complex, there is an extent to which today’s international system of scientific endeavour – the dependence on the boundless resourcefulness of the earth, the relations of power, the processes of intellectual collaboration and exchange –is a legacy of his engagement with Babel. In an era where the aeroplane is today’s ship, the image of so many of them grounded on the tarmac is a spectacular inversion of that produced by Van de Passe. For it shows us that, for the time being, the ship has headed back to port.

IV.

Since Augé wrote his book, there has been a seismic shift in the cultural reference points that dominate critical theory. Whereas then principally engaged with linguistics, semiotics, deconstruction, and human relations, it is today drawn to the sciences and mathematics. This new direction is motivated by the threat of an historical event like no other, environmental catastrophe on a planetary scale. The disciplines of biology, chemistry and geology have brought to our attention the Anthropocene thesis – the idea that humans have brought the earth into a new geological era. They have raised the spectre of global warming resulting from CO2 emissions, identified by ecologist Andreas Malm as ‘fossil capitalism’ (2015) and sociologist Bruno Latour as the climatic regime (Latour 2018).

The sciences have also shown that life and its environment is not as distinct as previously thought. The Gaia hypothesis, first advanced by atmospheric chemist James Lovelock and microbiologist Theresa Margolis in the 1970s posits that life, its ground and its atmosphere are a mutually constitutive and interdependent system (Lovelock 2000). There are no discrete, bounded parts of the system.

These insights have repercussions for the concept of presentness. The terrifying reality of climate change has diminished the capacity of the present to distract because it competes with and overpowers it. Nothing sharpens the mind like the threat of one’s own extinction. One of the effects is a revised sense of history and time. The stories that we tell about ourselves will need to be rewritten to incorporate new concepts: the natural, the planetary, ecology. With respect to presentness, the inference is that, long before the pandemic, it was already under threat. Dupont was living on borrowed time.

They (these insights) have also come to define new exploratory fields for the humanities that takes airports as a subject of critical investigation. The theory of interdependence tells us that the different elements of an airport – architecture, air, ground, machinery, power, radio signals and life forms – are not, as we have come to think of them, things in themselves. Rather, they make up a single, complex ontology governed by life processes. The airport is not architecture, nor technology, nor even landscape. It is a combination of organisms and their habitability conditions.

The ecological turn has also affected how it feels to fly. Aviation is an integral part of fossil capitalism, accounting for around 7% of the CO2 released into the atmosphere by humans. To continue to fly cognisant of this reality is to inhabit a radical contradiction. It is simply lazy thinking to talk about capitalism, violence, the Global North in the third person as if it had nothing to do with us. For sure, we are trapped, along with every other form of existence, in the machinery of contemporary capitalism that extracts value for the benefit of another. But this should not hold us back from the task of problematizing these relations from the inside. Before we knew of the Anthropocene our relationship with flight was already fraught with privileges and contradictions. We must now embrace them with significantly raised stakes.

V.

In April 2020 Purple Parking long stay on the Southern edge of the airport was taken over as a COVID-19 testing centre. It was one of many drive through facilities set up in the capital to enable the government to detect in citizens genetic material belonging to the virus through the polymerase chain reaction method (PCR). With an idle workforce to hand, an excellent road network and vast stretches of tarmac otherwise commercially useless at this point in time, airport car parks are an obvious choice of placement. I paid a visit.

I was greeted at the entrance by notices, white on red, stating that photography and filming was prohibited, and that car windows were to be kept closed. They were the type used by the Highways to guide motorists through roadworks and similarly held down with sandbags that hung from the frame. Masked staff stood under parasols at various points around the compound and beckoned me through a series of traffic cones. I passed a bus shelter where only a few weeks ago passengers would have waited for their terminal shuttle, and which had become an office. There were rows of white plastic tents supported against the wind with ropes attached to concrete blocks, and which had conical tops like those in paintings of medieval battles. The layout of my route would have served to slow and space vehicles had there been more of them. Yet, though I had booked the only slot available, I appeared to be the sole customer. I was brought to a stop at a white shipping container on which was printed a sunflower logo, yellow on green and the name Sunbelt Rentals. A man came out and held up a sign to say that I should open the window partially.

In possession of my test kit, I followed instructions to park up in a dedicated place to undertake the test. On completion of the nasal swab stage of the process, I discovered that the vial in which the cotton bud stick was to be inserted was just too short for the stick. I needed help. In my kit were instructions to put on my hazard lights. The man who responded to my blinking car held up with a board on which was displayed a phone number and the message: “Ring this number”. Through the windscreen a few seconds later I watched him reach into his pocket and answer the phone.

VI.

I have so far been exploring the experience of absence in an airport deprived of purpose. That purpose is the facilitation of flight by way of jet aircraft. Like any other form of transport, the technology used to achieve this centres on the production of power by releasing energy under controlled conditions. But unlike any other, in the form of the jet engine, it marks the upper limits of human capacity for the controlled release of energy to produce power, as well as the upper limits of dependence on an energy source that is not renewable. For no other technology is capable of generating, within the same time and space, the speeds necessary to get an aircraft into the air. Flight has come about because air has a lower viscosity than water, meaning that a vessel moving through it meet less resistance and can go faster. But this physical advantage comes with a drawback: speed is not a matter of choice: to stay afloat the vessel must move faster to avoid crashing to the ground. In this connection, we could think of the airport as an elaborate mechanism for harnessing power. And with its closure it might be possible to subsume the eliminated element in the term energy.

That energy should be the governing principle of a spatial order marks a radical departure from the wider reality. This is what makes it violent. In the mind of its engineers and administrators, the airport exists in a state of exception whereby the principle of entanglement is upheld, but life is shunted from centre stage and into the wings. We see this in the way that nature is constantly kept at bay. Since its designation as London Terminal Aerodrome in 1919, Heathrow, more than any other environment in Britain, has fought a daily battle with vegetation, birds, vermin and any other life form that threatens the designated land use. In some areas there is the appearance of nature: the runways are set in grassland; there are trees and hedges in the terminal areas and approach roads. But these are highly contrived. The grass is kept short to discourage voles. The tree species, mainly birch, are selected on the basis that birds prefer not to nest in them. To all intents and purposes, the organic quality of space, its complexity and fragility, has been almost comprehensively denied. Technology is imagined as ‘unencumbered’ (Schmitt 2015) by the biological and social reality of the world to which it belongs.

This exceptionalism also conditions the environment beyond the airport, some of it far afield. Mindful of its carbon footprint, in 2018 the airport adopted a carbon offsetting policy to be realised through the restoration of peatlands in Lancashire (Heathrow.com). It is as if the evolutionary history of an environment matters not, and one part can be substituted for another. The natural is partitioned off from the unnatural, the animate from the inanimate.

Also discarded is the rule book of sociological thought. According to this, the principal factors that shape our humanity are history, culture, political relations. Everything else we do stems from this. At the airport, these are supplanted by energy. Perhaps this is why Auge thinks of airports as non-places.

The virus has presented an alternative reality. It does not distinguish between spaces designated infrastructure hubs and those designated conservation areas. It sees no concrete runway where carbon may be released or peat bog where that release is offset. No perimeter fence or hinterland. It transcends such systems with indifference. So long as there are hosts that enable it to reproduce, it thrives. The virus leaves no doubt that the airport is alive and coextensive with the rest of planetary life.

VII.

Despite all appearances, the landscape is not a toxic one. The vast emptiness and the need for protective measures might evoke places such as Chernobyl or Fukushima, but the reality is quite different. Those places are uninhabitable. The high levels of radiation in the ground resulting from accidents makes them so. The view at Heathrow on the other hand is the spatial effect of an inversion. To be sociable, we must stay apart. To travel, trade and collaborate in the longer term, we must stop doing these things in the short term. Our absence ensures that the airport is the very opposite of toxic. But like the location of electrons in Schrodinger’s cat, the moment we stop to look, it changes.

Most ruins leave it for the spectator to ponder the cause of their demise. Heathrow is slightly different. Its singular function, the release of energy, points to a singular cause. If the airport can still be considered in any way ahead of the curve, it is because it is here, in the form of the pandemic, truths about our failure to acknowledge our complex relations with ecology show themselves first.

The virus’s indifference to the global – its withdrawal of judgement, its moral weightlessness – invokes capital itself. The comparison compounds the earlier observation about excess being rivalled only by nature. It is as if there is something structurally similar between nature and capital, as if capitalism shares part of its ontology with nature. If we are to follow the logic of this parallel, we must conclude that what is on view at Heathrow is not so much a standoff between capitalism and nature, but the contingency of the two. It reminds us too, if we are consistent, that Darwinism is as much a theory of the human imaginary as the body: the capitalist mind is continuous with the natural. These make important beginnings for rethinking ecology. For one, they put to bed once and for all arguments about our externality to nature. They point also to ways of studying nature from the inside. They necessitate for instance, the dissolution of a time-honoured dualism between the human and natural and its substitution with a new epistemology, one which places ecology as the political reality for landscape planners to come.

VIII.

Dupont is not the only figure caught up in the airport. In her 1997 photo essay In the Place of the Public: Observations of a Frequent Flyer artist and theorist Martha Rosler documented the departure lounges, walkways and aircraft interior that are integral to a career made possible by flight. She writes: “By the end of the 1970s… the art world required a lot of jetting about by artists for shows, and lectures. As an artist whose fare was paid for by various institutions, I all but abandoned the buses for airplanes’ (91). Rosler, not unlike Auge, is interested in the effacement of a certain kind of experience of travel and its substation with totalised industrial representation, a phenomenon which she traces, via Henri Lefebvre, to late capitalism.

By the turn of the Millennium the lifestyle Rosler describes for upwardly mobile US based artists had become familiar, native even, to a generation of European artists. The Scottish painter Carol Rhodes captured the transition in her landscapes of airports seen from aircraft. Marked by human activity yet devoid of people, Rhodes’s airports look hauntingly prescient today (Fig). My experience as a freshly milled art graduate pinpoints the date of my own aero mobility turn with some precision. In 1999 I undertook a residency at Wyspa Gallery, Gdansk, Poland, travelling 27 hours from London by bus. In 2001 I flew a similar distance to the Venice Biennale in 2 hours. The first journey cost me around £80. The second £7 each way, around the price of a McDonald’s meal. In 2003 I took advantage of the newly opened direct flight routes from London Gdansk to attend an exhibition and party at the Shipyard Gallery. I was benefiting from a new constellation of conditions that included deregulation of the airline industry – notably the prohibition of point-to-point flights, cheap fuel that flooded the market following the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the low interest that let start-ups get a hold in the market. By 2020 attendance at the burgeoning circuit of Biennials and residencies is routine, indeed, expected, for a professional for whom knowledge of the field and a community of practice is a prerequisite for contributions in the field. We may not go business class, but we fly regularly.

I foreground this history to implicate the artist in the scene I am describing. I am interested in the presence of the departed artist in the same way that a detective might be interested in someone known to have been at the scene of a crime. My intention is to position the artist as a user and beneficiary of the airport and displace the more familiar epistemology of observer from the side line.

As noted, art has historically engaged with site through the in-person presence of the artist and by making this public via documentation and exhibition. To the study of landscape, it brings the visible, sensory, and material. However, the phenomenon of the pause invokes another of art’s technologies of discernment, namely the logic of subtraction. The American land artist Michael Heizer made good use of this in Double Negative (1969-1970) an earthwork in the Nevada Desert. In the words of the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art, it consists of “two long straight trenches, 30 feet wide and 50 feet deep, cut into the “tabletop” of Mormon Mesa, displacing 240,000 tons of desert sandstone. The cuts face each other across an indentation in the plateaus’ scalloped perimeter, forming a continuous image, a thick linear volume that bridges and combines the “negative” space between them” (moca.org. n.d.). But what if, in the spirit of Heizer, we thought of the pandemic as a kind of artist who makes the quality of the landscape visible by taking something away? Within the scope of this imaginary, evidence of violence would be strongest in those sites the global economic system has deserted, places rendered remarkable not through the usual flux and flow but through stoppage. In which case, those parts of the city where movement is ordinarily most pronounced – shopping and sightseeing districts in the centre, airports, industrial zones and motorways in the periphery – promise the most spectacular view.

IX.

With the easing of lockdown in late June I visit the airport terminals. Terminal 5 is fronted by a Plaza on which sits a colossal work, Moving Worlds Night and Day. It is a 2008 commission by the British duo Langlands & Bell. Comprising two panels, one at either end of the concourse, it spells out airport codes from around the globe. They are written in neon and arranged in arcs, one per panel, which light up and dim again like a Mexican wave. Though the airport is open only for repatriation and cargo flights, no one has thought to switch the neon off. Its forlorn wave is made more so by the fact that it is also broken. A panel of shattered glass that forms the backdrop is threatening to fall to the ground from a height of about 3m. The area of plaza immediately in front of it is now closed off with crowd control barriers. Only there is no crowd to contain. Indeed, there is no one here but me. From close up, I realise that damage does not appear accidental. It has been hit by something heavy and hard. Something about the size of a brick.

Moving Worlds is one of many artworks owned by the airport. The majority were commissioned through the BAA art programme (1994-1998) and all of them are by British artists. Its stated function: “to enhance passenger, staff and business partner experience of airport environments and develop an art collection of national merit” (BAA Art Programme 1997: 1). This collection is complemented by another, that of the resident airline, British Airways who between 1995 and 2012 collected some 1500 works to increase brand awareness and a new contemporary image for the airline (artrights.me). Though contemporary with the critical investigations of Rosler and Rhodes, these initiatives took the integration of the artist and aviation in a new direction and to a new level. Unlike the critical investigations of Rosler and Rhodes, it established the artist as both a direct beneficiary of the industry and an advocate of the regime. This backdrop gives a revised sense of artist airport entanglement and of just how much has changed.

On arriving home, I notify Langlands and Bell by email of the damage to their sculpture. They tell me that they already know about it, having seen it a few weeks before on return from an exhibition in Ghana. They have no idea how it happened and sadly no one at T5 informed them about it. The artists are usually the last be informed about these events. They write on:

“As far as we remember the Contemporary Art Society, who acted as art consultants for BAA when we made it, negotiated or attempted to negotiate an agreement for the upkeep of the artwork. However, BAA was bought out by Grupo Ferrovial while we were working on the piece and these organisations never seem to keep the necessary systems in place to maintain artworks and manage these kind of issues when they arise.”[i]

Nobody then is responsible for the sculpture. There isn’t even someone with whom to cooperate, neither to cover it up, repair it, or remove it. The image of fluorescent barriers protecting a phantom crowd from injury may be one that lasts. It serves as a lamp that beams affectivity and emotional charge on the radical and uncompromising bordering imposed by nation states in response to the pandemic. On the line drawn through those lives and livelihoods that privileged the mobile over the sedentary. Similarly, its repair, should it take place, will be a measure of the shape of art’s financial relationship with the airport in a post COVID landscape. Who will pay, how much, to whom, and under what terms? In the very act of pointing to these questions the work assigns a role for public art post COVID. Any answers it might provide will bring the work new and unexpected meanings that endow it with much needed realpolitik. The deep irony of its misadventure is that, possibly for the first time since its conception, it can be called public art.

X.

In Spring 2021 the auction house Sotheby’s was appointed to sell prominent works from the British Airways Collection. It was deemed by now distasteful for an airline to harbour luxury goods while negotiating mass redundancies. The auction held on July 21 would include paintings, prints and works on paper by Young British Artists Hirst, Marc Quinn, Peter Doig, as well as the much-publicised Cool Edge by Bridget Riley, a painting that had once hung in the Concorde Room.

Perhaps the writing was on the wall, had we known how to read it. Imagine You’re Moving (1997) is a work by Julian Opie in the Flight Connections Centre at Terminal 1. It offers passengers a paired down landscape of fields and trees displayed on light boxes and the monitors that otherwise display flight information. It says something like: “somewhere other than this. A place spared of aircraft, and crowds, and concrete.” I have seen the work only as an image but recall how my encounter stirred in me both respect and irritation. Respect that the artist had managed to hijack a space reserved for semiocapitalism. Irritation at the hypocrisy of a commission that contributes to the very problem from which its subject matter promises delivery. If Opie likes the bucolic why does he bolster the reputation of airports? And why if he is such a clever semionaut, has he lowered himself to the level of builder in a ‘desert of cities’ (Baudrillard 1994: 153).[ii] Since the pandemic, however, this work feels very different. I had previously thought that this could be pretty much anywhere. But the pandemic has got me thinking a bit harder about the priori condition of British authorship. These are evidently England’s merry green fields in a renationalised, post globalized world. Thus far it is clear with hindsight that they signalled over a quarter of a century ago the presence of a dying system of open borders, integration, and pointed with cheery melancholy to the ruins in which I am standing today.

XI.

The airport in lockdown is set in relief by cultural revival in the surrounding neighbourhood. Bushy Park, to the south is teeming with children’s dens. Children have always made dens in this park. But I do not recall them in such numbers. Structures such as these point to a socio-cultural world of making against which official and/or administered arts are poised. Park dens rather than MoMA Heathrow, they seemed to say. The analogy of neurogenesis is useful. Just as, following a stroke, the brain establishes new neurological pathways, so, following the failure of cultural systems, other forces – curiosity, the imagination, and socially productive energies find fresh ways in which to exist.

Along the banks of the Thames, for instance between Kingston and Teddington Lock, also to the South, are more constructions. Some are built for thrill, for losing control. I try a rope swing and feel a release to the experience of confinement. It invokes the vertiginous slides of Carsten Holler that introduce a moment of madness, what Roger Roger Caillois had in 1958 described as “an attempt to momentarily destroy the stability of perception and inflict a kind of voluptuous panic upon an otherwise lucid mind. In all cases, it is a question of surrendering to a kind of spasm, seizure, or shock which destroys reality with sovereign brusqueness” (Caillois 2001).[iii]

Considerable time has gone into making these swings. Also, money for rope, screws, and timber. One swing hangs from a branch about 12m up. There are no low branches on the trunk, meaning that it was installed by someone with equipment such as that used by a tree surgeon. The autonomy, formal diversity, and social capabilities of these subaltern interventions contrast favourably to commissions conditioned by the airport’s administered, market-led, internationally orientated, and state-backed patronage. They provide a glimpse of horizontally structured, carbon efficient cultural practices conspicuously lacking in art funded by multinationals. It is a picture flanked by others of cultural autonomy, flânerie and mutual aid, qualities that art criticism since the mid-1990s has associated with contemporary art’s political promise. To this extent, we could think of the pandemic as an instrument that has debordered art and life.

XII.

In his critique of urban planning under the Creative City concept, Jonathan Vickery enlists the deficit in creative energy among bureaucrats and engineers as its fundamental shortcoming. The pandemic has foregrounded others, specifically the mercurial nature of global corporations in times of duress, and the vulnerability of aviation’s economic model for arts funding. The misadventure of Moving Worlds points to the need for relations with resilient and accountable organisations, whose priorities are the commitments that they have made. By nature, national and regional governments are best placed to deliver this. Heathrow’s abandonment of the arts stands in stark contrast to the public funding hurriedly distributed to beleaguered arts institutions by the Arts Councils or to grassroots initiatives such as the Artist’s Support Pledge that sought to support artists themselves. Thus, the pandemic has pointed to how art’s relationship with hegemony might be reset, as well as its relationship with the planet on which it is sustained. It has offered new beginnings that the political left has sought, even if not in a manner widely advocated.

It is now apparent that what is ahead in the airport landscape is behindness. Here, truths about our failure to acknowledge our entanglement with ecology show themselves first. Here the displacement of the analogue by the digital is most pronounced. Of course, the airport as metaphor for a future present has been under threat for a while. This imaginary belongs to the last century, and surely came to an abrupt end with 9/11. Yet the values it has nevertheless helped nurture live on in systems of international cultural exchange: museum loans, artist residency programmes, art fairs and biennials, to name just a few. It is an arrangement that has enabled artists to cultivate intellectual capabilities and politically circumscribed personas on an international stage. It is also an arrangement that has underpinned the concept of the contemporary in art, by which I mean the proposition that artists can be together in time. There would seem to be a binding relationship – a sine qua non – between contemporary art and airports. In which case, at large, and also at stake, in the airport landscape is now the figure of the contemporary artist.

However, a reinvigorated localism is not a future to celebrate. At least not on its own. The ubiquity of the park dens detracts from the fact that opportunities for making such structures remain uneven. Not everyone lives by a park or a river. Not everyone has the time to play. If you do not have financial support, through a gallery or grant, you won’t be able to carry on. The dens are also limited aesthetically. They may look different in relation to each other, but this diversity is nothing compared to that available through curated programmes, and workshops such as those at Watermans Arts, a publicly funded arts centre just East of the airport. The boundary between the professional and the amateur is essential if this diversity is to survive.

The climate crisis needs people capable of thinking locally and globally. David Harvey’s concept of ‘militant particularism’ is useful (1995) on this account. For Harvey grassroots militancy around a local issue, for example the closure of a car plant, has the potential to translate into a more consequential movement across space and time. The realisation of this potential requires networked, strategically positioned intellectuals who are also sympathetic to the local issue to connect movements up. The car plant in Harvey’s example might easily be the threat of airport expansion and today’s professional artist might easily be one such intellectual.

Post Script.

On a visit to Heathrow in the Autumn of 2021 I found the Mustang gone. To my surprise I felt a sense of loss and immediately sought to comfort myself by seeking to track it down. I knew my efforts were futile but thought I might be reassured in the knowledge that it was still alive. I visited the website of the Government’s Driver and Vehicle Licencing Agency (DVLA) and punched the registration plate into the vehicle enquiry page: DU17 JKY. A bold sans serif text, black on grey, reported back:

Vehicle details could not be found

The line of grounded aircraft disappeared the same summer, though I knew that they could not be back in service, at least not all of them. Which is perhaps why, while holidaying at Porth Mawgan, Cornwall, the sight of aircraft across a field caught my attention. They were incongruous in the rural setting, Surreal even, a juxtaposition enhanced by the fact that to see them I needed to negotiate a herd of cattle who had congregated around a gate, seemingly waiting for me to feed them. One of the aircraft caught my attention. It was a 747 printed up with the words “One World”.

The damage to Moving Worlds does not appear accidental. The glass has been hit by something heavy and hard. Something about the size of a brick. TBC

The airport in lockdown is set in relief by cultural revival in the surrounding neighbourhood. Bushy Park, to the south is teeming with children’s dens. Children have always made dens in this park. But I do not recall them in such numbers. Structures such as these point to a socio-cultural world of making against which official and/or administered arts are poised. Park dens rather than MoMA Heathrow, they seemed to say. The analogy of neurogenesis is useful. Just as, following a stroke, the brain establishes new neurological pathways, so, following the failure of cultural systems, other forces – curiosity, the imagination, and socially productive energies find fresh ways in which to exist.

Along the banks of the Thames, for instance between Kingston and Teddington Lock, also to the South, are more constructions. Some are built for thrill, for losing control. I try a rope swing and feel a release to the experience of confinement. It invokes Yves Klein’s Leap into the Void or the vertiginous slides of Carsten Holler that introduce a moment of madness, a so called “voluptuous panic upon an otherwise lucid mind” (Tate Modern). Considerable time has gone into making them. Also, money for rope, screws, and timber. This swing hangs from a branch about 12m up. There are no low branches on the trunk, meaning that it was installed by someone with equipment such as that used by a tree surgeon. The autonomy, formal diversity, and social capabilities of these subaltern works contrast favourably to commissions conditioned by the airport’s market-led, internationally orientated, and state-backed patronage. They provide a glimpse of horizontally structured, carbon efficient cultural practices, and precisely when the state and multinationals have failed. We could think of the pandemic as an instrument that has debordered art and life. Taken together, they paint a highly seductive portrait of a neighbourhood in which administered, international arts are superfluous. It is a picture flanked by others of cultural autonomy, flânerie and mutual aid, qualities that art criticism since the mid-1990s has associated with contemporary art’s political promise.

In his critique of urban planning under the Creative City concept, Jonathan Vickery enlists the deficit in creative energy among bureaucrats and engineers as its fundamental shortcoming. The pandemic has foregrounded others, specifically the mercurial nature of global corporations in times of duress, and the vulnerability of aviation’s economic model. The misadventure of Moving Worlds points to the need for relations with resilient and accountable organisations, whose priorities are the commitments that they have made. By nature, national and regional governments are best placed to deliver this. Heathrow’s abandonment of the arts stands in stark contrast to the funding provided by Arts Council England to beleaguered arts institutions. Thus, the pandemic has pointed to how art’s relationship with hegemony might be reset, as well as its relationship with the planet on which it is sustained. It has offered new beginnings that the political left has sought, even if not in a manner widely advocated.

It is now apparent that what is ahead in the airport landscape is behindness. Here, truths about our failure to acknowledge our entanglement with ecology show themselves first. Here the displacement of the analogue by the digital is most pronounced. Of course, the airport as metaphor for a future present has been under threat for a while. This imaginary belongs to the last century, and surely came to an abrupt end with 9/11. Yet the values it has nevertheless helped nurture live on in systems of international cultural exchange: museum loans, artist residency programmes, art fairs and biennials, to name just a few. It is an arrangement that has enabled artists to cultivate intellectual capabilities and politically circumscribed personas on an international stage. It is also an arrangement that has underpinned the concept of the contemporary in art, by which I mean the proposition that artists can be together in time. There would seem to be a binding relationship – a sine qua non – between contemporary art and airports. In which case, at large, and also at stake, in the airport landscape is now the figure of the contemporary artist.

Despite all that has been seen and said, a reinvigorated localism is not a future to celebrate. At least not on its own. The ubiquity of the park dens detracts from the fact that opportunities for making such structures remains uneven. There is all the difference between economically viable and non-economically viable versions of them in the long term. If you do not have financial support, through a gallery or grant, you won’t be able to carry on. In aesthetic terms they are also limited. They may look different in relation to each other, but their diversity is no match for that provided by curated programmes, such as those at Watermans Arts, a publicly funded arts centre nearby. In which case, a boundary between the professional and the amateur is essential for social mobility.

Whatever the hypocrisies inherent in contemporary art, however small the pool of supported artists may be, it sustains nevertheless a myriad of intercultural relations in an international arena. Travel disrupts territorial forms of order. It creates unexpected encounters that bring into proximity values that are often mutually exclusive. It is adjacency, often dissonant and uncomfortable, that residencies and international collaborations make possible.

The multiplicity of histories written through contemporary art stands over and against a cannon of Euro-American Modernism that is in urgent need of challenge. At stake in the curtailment of the contemporary is art’s capacity to speak to post-colonial discourses and to the social justice agendas that they underpin. The fact that contemporary art frequently functions to wash regimes and corporations makes art’s contribution in these areas more difficult, but it does not negate them.

Related to this is art’s ability to challenge neo-conservatisms that accompany the sedentary. The loss of international collaboration plays directly into the hands of nationalism – what David Harvey refers to as ‘militant particularism’ – a reactionary politics for which ‘think local’ is a way of rejecting the liberal commitment to inclusivity and diversity. Debates that might ordinarily transcend politics – the value of the local, the sustainability of global air travel – stand against vaccine nationalism, de-globalisation, and anti-immigration. From these observations a new question emerges: How can we reimagine art capable of fighting the climatic regime, while continuing to bring together knowledge of the world, from around the world?

[i] Slager, H. 2015. The Pleasure of Research. Hatje Cantz Verlag.

[iii] Here I am interested in whether evidence of violence in artist and environment relations might be strongest in those sites the global economic system has deserted, places rendered remarkable not through the usual flux and flow but through stoppage. If so, those parts of the city where movement is ordinarily most pronounced – shopping and sightseeing districts in the centre, airports, industrial zones and motorways in the periphery – promise the most spectacular view.

[i] Philosopher and Sociologist Bruno Latour is in the latter camp. In an article of March 30, Protective Measures, he has encouraged us to reflect on what we would not want to go back to after the pandemic has passed. (2020).

[ii] For a discussion of the relevance of FA’s methodologies to the Anthropocene. See Turpin, E. (ed). 2013. Architecture in the Anthropocene. Encounters Among Design, Deep Time, Science and Philosophy. Open Humanities Press. Especially. pp 63 – 83. Matters of Calculation. The Evidence of the Anthropocene. Eyal Weizman in Conversation with Heather Davis and Etienne Turpin.

[iii] Here I draw on the American land artist Michael Heizer, particularly Double Negative, 1969-1970, 240,000-ton displacement of rhyolite and sandstone, Mormon Mesa, Overton, Nevada.

[i] See for example, Osborne, P. 2013. Anywhere or Not at All. Philosophy of Contemporary Art. Verso.

[i] Email correspondence with the author.

References

Benjamin, W. (2009). The origin of German tragic drama. London: Verso.

De Saint Simone. 2010. [1825]. Opinions Litteraires, Philosophiques et Industrielles. Kessinger Publishing

Dunne, J. 1950. An Experiment with Time. Faber

Heathrow.com. n.d. Available at: https://www.heathrow.com/latest-news/heathrow-announces-its-first-culture-curator-reggie-yates

Latour, B. 2020. Protective Measures. Cultural Politics (2021) 17 (1): 11–16. Available at: http://www.bruno-latour.fr/sites/default/files/downloads/P-202-AOC-ENGLISH_1.pdf

Malm, A. 2015. Fossil Capital: The Rise of Steam-Power and the Roots of Global Warming. Verso

Marker, C. 1962. La Jetee. Nouveaux Pictures

Parveen, N and Walker A, 2020. Temporary mortuary being built at Birmingham airport. The Guardian. March 27, 2020. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/mar/27/temporary-mortuary-being-built-at-birmingham-airport

Rosler, M. 1998. In the Place of the Public: Observations of a Frequent Flyer. Cantz

Schmitt, C. Dialogues on Power and Space, 2015. ed. Kalyvas, A and Finchenstein, F. Polity Press.

St. John Mandel, E. 2015. Station Eleven. Picador.

University of Cambridge. https://www.esc.cam.ac.uk/research/research-groups/cambridge-volcano-seismology/all-about-earthquakes-and-volcanoes

Virilio. P. 2005 [1984] Negative Horizon. Trans. Michael Degener. London and New York: Continuum

Watling, T. 2021. Heathrow Airport a ghost town as passenger traffic down 90%. The Mail Plus. Available at: https://www.mailplus.co.uk/edition/travel/travel-news/85000/heathrow-airport-ghost-town-passenger-traffic-down

A version of this blog was also presented as After the Airport City. Thinking Art and Mobility Post COVID-19, RGS IBG Borders, Borderlands and Bordering. August 2021

Some images were presented at Im/mobile Lives in Turbulent Times. Methods and Practices in Mobilities Research. Northumbria University. July 8 – 9 2021. Curated Kaya Barry and Jen Southern. Available at: http://wp.lancs.ac.uk/art-mobilities/nick-ferguson/